PROVIDENCE — Father Raymond Tetrault is being remembered for his strong support of the Hispanic community and for his talents as an artist

Father Raymond, as he was known, died on January 3, surrounded by his close friends, his brother priests and members of Rhode Island’s Latino community. He was 87, two days shy of his 88th birthday.

Mario Bueno, executive director of Progreso Latino Inc., was one of those close friends at Father Raymond’s bedside in his final moments.

He had known Father Raymond for more than 40 years, since he was a child growing up with his family near St. Michael’s Parish in South Providence, where Father Ray ministered to those living in the neighborhood, especially the Spanish-speaking community.

Father Raymond was so highly regarded by his family that he was asked to serve as Bueno’s Confirmation godfather.

“He was a mentor to a lot of young people in the community in Providence. That’s how I met him,” Bueno said.

“He learned the language. He knocked on people’s doors in the neighborhood and the story is that someone said, ‘I would like to have Mass in Spanish at my house,’” Bueno said of a recent immigrant from Santo Domingo. Father Raymond then started the Mass in Spanish at the church.

Father Raymond showed his care for the Latino community not just by offering Masses in their language, but also through his support for their needs on the home front.

He started Communidades de Base, a grassroots community group for those living nearby.

“People would set up by neighborhood and they would go visit each other and they would have prayer in each other’s homes on a weekly basis. That’s what he started there at St. Michael’s,” Bueno said.

“He had a big influence in me in looking at labor organizing and community organizing as something to do that was important in the community,” said the director of Progreso Latino Inc., an organization based in Central Falls whose mission is to help Rhode Island’s Latino and immigrant communities achieve greater self-sufficiency and socio-economic progress by providing transformational programs that support personal growth and social change.

Bueno said that Father Ray’s vision was that we are all responsible for one another on a local level as well as a global level. He sought to make people aware of how important it was to be actors, not just watch from the sidelines in helping their communities.

“We’re supposed to make this world we live in a better place. We can’t wait for God to come fix everything for us, it’s up to us to fix it. That was his teaching,” Bueno said of Father Ray’s spirituality.

Father Ray also had a keen interest in what was happening in Central America and encouraged people to come up with ways of putting their faith into action by helping those in need there in any way they could.

“He was an extraordinary priest,” Bueno said. “He was a living example of what we should be doing in our communities.”

Father Ray was raised in the Lippitt Hill neighborhood of Cranston, the son of Conrad and Elizabeth Carroll Tetrault. He was one of five children and is survived by his brother Joseph and his wife, Maria of Glastonbury, Connecticut. He was predeceased by his sister Irene Meenagh of Coventry and two brothers, Conrad of Costa Mesa, California, and Leon of Cumberland. He has many nieces and nephews: Robert Tetrault, Dawn Sather, Lynn Winstead, and Sharon Lepore, all in Southern California; Stephen Meenagh of Coventry; Suzanne Christensen of Boston; and Leslie Christenson of New Hampshire. He had 10 grand and great-grand nieces and nephews.

Father Ray’s early education began at the Holy Name School in Providence, followed by LaSalle Academy, Our Lady of Providence Seminary, and the University of Louvain in Belgium, where he was ordained a priest in 1960.

His ministry as an ordained priest was wide-reaching. He taught English and algebra at the high school seminary before becoming superior and Novice Master of the “Brothers of Our Lady of Providence,” a newly formed society in the diocese committed to working with the poor and the increasing number of new immigrants in the city.

He would go on to serve the needs of those immigrants in the neighborhood around St. Michael’s Church for 50 years.

“Father Raymond’s ministry with Latino immigrants led him to join them in their struggle for justice in American society,” said Father Robert Beirne, a friend of Father Ray for 70 years.

Father Beirne said that Father Raymond helped to develop new leaders who came forward.

“Latinos discovered that their lives mattered and that it was possible for them to achieve decent and productive lives. His embrace of the principles of non-violence, of living a life of peace and embracing justice became the foundation of his life,” he said.

Father Beirne said that his friend was in awe of creation and cherished the environment, finding simple pleasure in working in his garden, feeding the birds outside his window, and nurturing the lemon tree that grew there.

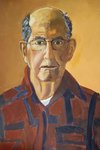

Father Raymond developed a passion later in his later years for expressing himself through art.

About a year ago at Christmas, Father Raymond surprised his 10 housemates at the St. John Vianney retirement home for priests, on the grounds of Our Lady of Providence Seminary, by presenting each with a painted portrait he had done of each of them.

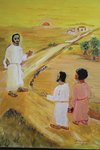

He began by painting many religious scenes depicted in the Bible, such as the Wedding Feast at Cana and the Road to Emmaus.

He also created traditional still life and self-portraits.

As a painter, Father Raymond shared his vision of nature and of the suffering people of the world, depicting injustices he perceived.

He incorporated some of his observations on the way Blacks and Latinos are viewed and treated in society into some of his works.

About three months ago, shortly before Father Raymond went into the hospital, Father Beirne encouraged him to display some of his works in an exhibit.

As his friend gestured to the dozens of works around him that he had already created, he expressed a desire to continue working on new ones.

“He said, ‘I can’t, I’ve got so much more to do’,” Father Beirne recalled.